Deep Water, White Bass & the Meaning of Life

Fighting the current and inexperience, the author takes on the spring run with a little help from his friends. Here's how to do it right.

The river is running chilly and hard. Not high, but with some shoulder. The White bass are running and it’s now or never, they won’t last long. They come in the spring, when the Indiana weather is unsteady.

The year is 1993. My 10-year-old self is almost up to his armpits in the current, moving deeper, straining to get within a short cast of the fish. I’ve got a fly rod in my right hand, line pinched under my index finger, both elbows high keeping my shirtsleeves from getting wet.

Two experienced hands, my Father and our friend Jack Spaulding, watch my progress – or lack thereof.

A long cast would reach the far bank without going too deep. But this is my first time working out the puzzle of wading and fly fishing; long casts aren’t in the cards. With water up to my chest, simply casting would be a success. Catching a White bass and not filling my waders with cold water from the East Fork of the Whitewater River would be Christmas morning.

All rivers are characters in the story of the landscape, this one even more so. The East Fork cuts south through the Whitewater Valley on the edge of central Indiana, not far from the Ohio line. History runs near the surface in this part of the state. Impressionist T.C. Steele painted the Whitewater Valley just before the turn of 20th century. The subtle, untamed, beauty he found over 100 years ago is still there.

In 1974 the Army Corp dammed the East Fork for flood control just north of Brookville. The reservoir covers a little over 5000 acres. It’s pretty, like a small version of the huge impoundments in Kentucky and Tennessee, long and narrow with fingers reaching off into wooded drainages.

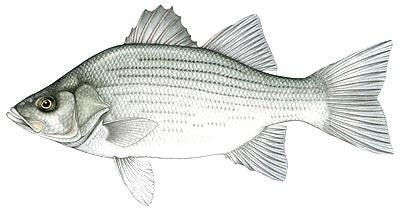

In late April, early May, the White bass run up, out of the reservoir, and into the river to spawn. They come in droves, ten of thousands, I’m not sure. But once a year, for approximately a couple weeks, they dominate the lower part of the river. When the water temperature reaches the mid-50s this temporary migration happens all over the Midwest and beyond.

Spring rains bring the magic temperature, but often return to blow out the river, running out the clock on fishing. So when it happens, you go.

If the conditions are right, the fishing is easy and fast. Hundred fish days can be true and fishermen sometimes retire early complaining of tired arms and the monotony of catching a fish on every cast.

But “easy and fast” is on a sliding scale nested inside the baseline difficulty of river fishing. Bobbers and bluegills it isn’t.

A fly rod delivers life-like presentation but comes with complexity that is by nature a mess. The trick is turning the mess into something worth more than the sum of its many parts. Done well it’s beautiful, and looks deceptively easy.

Independent of fishing, wading is a skill of its own. Some people never take to it. Only so much water can be fished from the bank. But in the river, minding depth and current, you’re free to roam at will.

The initial sensation of water pressing around you, increasing as you step deeper, confirms the river’s in charge. You can almost never see your feet, so there’s a technique of feeling as you go along. And it’s work. Just moving through the water takes effort, pushing against current is exercise.

Finally, there’s the real possibility of screwing up and going downstream. Learning how deep is too deep, how much current is too much, can’t really be explained. Finding your limit is a balance of risk tolerance and experience.

Despite, or maybe because of, the challenges, my Father chose to introduce me to river fishing during the run. It’s not a guaranteed success, but If you get your technique correct, do everything “right,” in so far as that counts in angling, these fish will usually cooperate.

Also Read: Tying your own flies is rewarding, and easier than you think // Our Fishing Editor explains why tying flies can improve your fishing. Here’s how to get started.

Fighting the current, my younger self battled on. But a mind, especially a young one, can only focus on so many things at once. I wanted a fish. I wanted to make the men with me proud, and most of all I wanted to be successful in this world I was enamored with.

As an outdoor writer, our friend and fishing partner Jack Spaulding is a scribe of that world. He falls into an increasingly rare category: A master of traditional outdoor articles and stories.

Weaving local color, humor, and practical knowledge into a few hundred words, his writing captures a time and place before my generation. A romantic world where half-wild kids grew up on the river, access was a given rather than an exception, and outdoor writers had weekly columns in every newspaper. These things are mostly in the past.

With my companions close, but not too close, on I went. Getting pushed around in the current, water near the top of my waders. Getting unbelievable knots in the snarl of fly line floating around me. Getting my fly hung in overhanging trees, on the bank, on submerged logs. Dropping casts and starting over. Not casting far enough or blowing the mend. Not waiting long enough for my streamer to sink. Not casting upstream at the correct angle. Not stripping the line with enough snap to make the fly dart and stop, dart and stop.

Spaulding quietly observing, my Father paused his own fishing to give me one of the day’s many streamside casting tune-ups, sending me back out with a few words of encouragement and renewed confidence.

But time was tight. The sun slipped down into the trees, casting faint shadows, the undercut banks starting to dim. We’d have to pack up soon. While my Father was feigning nonchalance, Spaulding was taking mental notes.

Not long after, he wrote about our trip in his weekly syndicated column. It even included a photo, black and white. So this is the second time our fishing trip made it into print, just 29 years and a world apart.

The framed article still hangs in my Father’s study. I’ve seen the story a thousand times, but it never fails to stop me. A time machine in glass, wood, and paper.

I don’t know if I remember what happened in those last few minutes of fishing, or if his article has slowly enveloped it. Either way, Spaulding told it first and I can’t top it:

As the man quickly unhooked and strung his sixth white of the morning, he looked at his watch and reluctantly said, “We have about 10 more minutes to fish!”

As the words echoed along the river bank they were cut short with a resounding, “YEEOWEEE, Dad, I’ve got one!”

With 7 feet of fly rod bent into a large “C” shape, the small boy struggled with what would prove to be the largest white bass of the day.

Quickly wading upstream to lend any needed assistance, the father was wearing a grin even bigger than his son who strained against the powerful runs of the fish.

Soon the fish was alongside and the boy beamed in telling the details of the strike and the ensuing fight to his father.

Later I had the opportunity to ask the boy how he liked flyfishing for whites. His reply was exuberant as he said, “It’s the greatest especially when you have someone to show you how!”

Four years later Spaulding gave me my start in the writing business. Things progressed from there.

How to Fish the Run

The first task is finding a location where the White bass run up out of a larger body of water into a river, and then timing it correctly. White bass are widely distributed across the U.S. and parts of Canada, so the fish aren’t hard to find.

Warming spring water temperatures trigger the run, science indicates mid-50s will do it. In practice, however, just keeping an eye on your river of choice is the best way to time it correctly. In Indiana this typically happens in May. Local knowledge is hard to beat. Guides, tackle shops, online fishing forums and groups can be indispensable if you or your fishing buddies can’t check in person.

When they’re in, they’re hard to miss. If the water is clear you might see the fish. But more often, a quick test fish will tell the tale.

We’re fishing the run in central Indiana, so geography may require different tactics, but here’s what works in our area.

Weighted streamers on a sink tip line are necessary to get the fly down in the current. Anything less and you’ll be above the fish.

Clouser minnows in sizes 6 through 10 are a good place to start. The Shadley Streamer (my Father’s creation) is a local favorite. It’s tied on a streamer hook (also sizes 6-10) with a white marabou tail, a silver mylar tubing body, and a white chenille head. Wrap .020 or 0.030 lead wire under the mylar body.

Tapered leaders aren’t necessary, a 5-foot length of 3x tippet will do.

A 5, 6, or 7-weight rod, depending on your preference, is what you’ll need.

Wading is a necessity, especially for fly fishing. Stocking-foot chest waders and appropriate wading shoes are the best bet. Remember, if you take a spill and fill your waders with water, don’t panic. Water on the inside of your waders doesn’t weigh any more than water on the outside – you won’t sink. Keep calm, regain your footing, and sheepishly go dump your waders.

You’re casting to cover much like smallmouth fishing. Target outside bends, cut banks, downed timber, and rocks as long as there’s enough depth to hold fish.

Cast upstream at about a 45 degree angle, mend quickly before too much of the sink tip goes down, and give it short, sharp strips with a brief pause between. You’ll probably need to wait at least a few seconds for the fly and sink tip to get down before starting the strips.

We usually catch and release, but some folks keep them to eat. Maybe our palettes aren’t sophisticated enough, but they tend to just taste like, well, fish.

Ben Shadley is Editor & Publisher of The Sportsman.

Very charming:)Whitebass taste like chicken:))

Thanks Ben for a great story.

All the best. MICK